Last week, the Department of Homeland Security announced it planned to eliminate the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which among other crucial responsibilities, manages the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Since 1968, the NFIP has offered subsidized insurance policies to homeowners in flood-prone areas where the cost of private insurance policies is too high. Today, it holds 4.7M policies and $1.3T in liabilities. Without the NFIP, many homeowners in flood-prone areas would struggle to secure mortgages because lenders typically require flood insurance or charge higher interest rates to offset the flood risk. If the NFIP is dissolved, the gaps would need to be filled with alternative insurance solutions.

Indemnity Insurance Shortfalls

In 2023, 62% of global economic losses due to natural catastrophes were uninsured, and in the US, 42% of such losses were uninsured. The protection gap is the difference between insured and uninsured losses and indicates how resilient communities are to disasters. As climate disasters have become more frequent, severe, and unpredictable, insurance risks are harder to predict and insurance policies are more expensive, leaving gaps in the market. Private insurers are required by law to balance the rising risks with revenue from premiums, but state regulations cap the premium hikes insurers can charge. Therefore, as risks grow, insurers limit coverage in high-risk states, especially those with stringent state regulations.

For example, major insurers like State Farm and Allstate have reduced coverage in California due to wildfire risks, and Progressive and AAA have scaled back in Florida due to storm risks. In the US, banks do not issue mortgages for uninsurable properties, so insurance is essential for the housing market to function.

Solutions to Address Coverage Gaps

Property Resilience

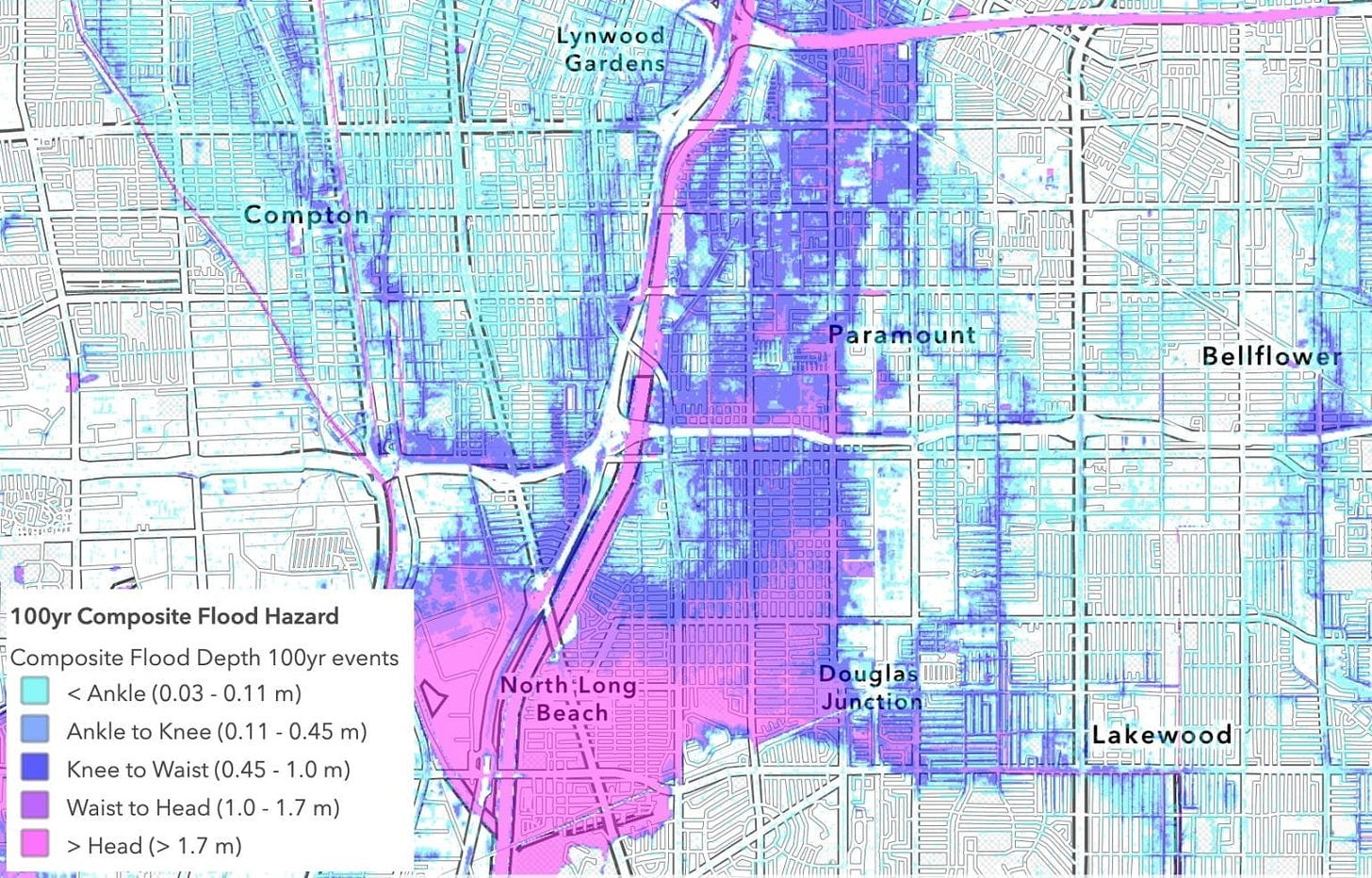

Homeowners can retrofit their homes to withstand disasters, including by building with ignition resistant materials in fire zones and elevating houses with stilts in flood zones. Insurance companies can discount these costs and state and local governments can update building codes, but the costs are high and do not completely prevent damages.

State-Backed Insurance

As private insurers limit coverage in high-risk states, state-backed last resort insurance programs have grown. Since 2018, they have doubled in market share and hold over $1 trillion in liabilities, including $525B in Florida and $290B in California. However, many states do not have clear plans for how they would pay out the sums.

Also, last resort policies are only offered for homes worth up to $1M-$3M depending on the state. For homes worth more, another option is non-admitted insurance.

Non-Admitted Insurance

Non-admitted insurance is lightly-regulated insurance where states do not monitor the quality of the insurers, review contracts, or limit price hikes. Also, non-admitted insurance are not backed by guaranty funds that ensure customers get payouts for their claims even if the insurer goes bankrupt.

Premium Adjustments

To limit exposure to short-term premium hikes for residents, government and state-backed insurers have practically subsidized homeowners for decades. Raising premiums to reflect climate risks could stabilize the market but would push many people to relocate.

What is Parametric Insurance?

Parametric insurance offers an alternative to indemnity insurance. Unlike indemnity insurance, which covers actual losses, parametric insurance covers the probability of a damaging event happening and triggers payouts based on predetermined parameters. The insured pay a premium based on the likelihood of an event occurring instead of on the vulnerability of their assets, and if the parameter is reached or exceeded, the insured are eligible to collect payment.

The parameters must be objective measures that are reported by independent third parties and correlated to the events that cause financial loss for the insured. These include magnitude for earthquakes, wind speed for tropical cyclones, and water depth for floods. Third parties include, for example, the Japan Meteorological Agency for reporting seismic intensity, the US Geological Survey (USGS) for reporting earthquake magnitude, and Moody's HWind for reporting wind speeds.

Parametric Insurance Benefits

There are several benefits of parametric insurance.

Quick Payouts

Parametric insurance often provides access to liquidity within days of an event, without the long damage assessments and claims processes of indemnity insurance. This provides effective relief and faster recovery.

Flexible Coverage

Parametric insurance can cover hard-to-model losses in traditionally underinsured sectors like tourism, renewable energy, trade, and agriculture as well as events where underwriting assets is challenging and financial exposure is difficult to assess, including expenses for immediate relief, evacuation, and mitigation.

Transparency

Payouts are based on objective and verifiable third-party data and do not require damage assessments.

Lower Costs

Parametric insurance reduces administrative overhead and expenses related to claims.

Customizable

Triggers and payouts can be tailored for specific risks. Also, the payouts can be used to cover any economic loss, which gives the insured more flexibility. For example, even if the insured’s property is not damaged, they can direct funds to child care if schools closed due to the event or to make up for lost work days due to damaged roads.

Parametric Insurance Limitations

Proof of loss requirements

Parametric refers to the trigger type that leads to a payout and is not limited to insurance – most derivatives use parametric triggers. In the US, for parametric policies to be considered insurance instead of financial speculation, they must have proof-of-loss requirements, in which the insured are paid only if they can prove they have suffered a loss. The key is to make the process quick and easy, like confirming damages through a text message from the insured or through drone or satellite imagery.

Consumer Literacy

Consumer education, especially for residential consumers, can help the insured understand the range of triggers and payouts and the differences between parametric insurance and the more familiar indemnity insurance. Also, insurers market parametric insurance as a complement instead of a substitute to traditional homeowners insurance to show that it increases coverage and fills gaps where traditional insurance falls short instead of replacing indemnity insurance altogether. Larger businesses and governments may have a better understanding of parametric insurance.

Basis Risk

Basis risk arises when a parametric insurance payout does not align with actual losses. Small deviations in parameters can prevent payouts even when there are substantial losses, and payouts greater than damages may be taxable.

For example, Hurricane Beryl caused significant damage in Jamaica in 2024, but a World Bank-backed catastrophe bond that could have paid out $150M missed the payout trigger by nine millibars, leaving Jamaica with nothing.

Since payout size depends on the premium, communities with limited financial resources often receive smaller payouts that may not fully cover their losses, even when a payout is triggered. Parametric insurance policies can be more expensive when offering broad coverage, and they carry basis risk, while indemnity policies expose the insured to deductibles and exclusions but offer more predictable coverage.

Basis risk can be reduced through consumer education, proof-of-loss requirements, and structure design like double triggers and staggered payouts. Double trigger design requires meeting two independent parameters for payout, which limits false positives and negatives. Staggered payout design distributes payouts in tiers based on severity of triggering event instead of using a binary structure.

Data Reliability

In parametric insurance policies, the insured pay a premium based on the likelihood of an event occurring. Insurers therefore try to model and price weather events accurately using advanced computing, satellite imagery, and AI. However, the data and models used for simulating and predicting complex interactions between factors can be flawed.

For example, Malawi declared a state of disaster in 2016 due to a drought that affected over 6M people and met the parameters for a payout. However, they received no payout because the African Risk Capacity (ARC)’s model used long-cycle maize instead of short-cycle maize in its model and therefore underestimated the number of people affected. Although the ARC adjusted its model and Malawi eventually received a payout, the delay caused significant damages.

As climate change leads to more uncertainty, insurers seek forward-looking models as well as historical data to predict risks. However, most private risk modelers protect their intellectual property and do not allow independent reviews, even though the decisions informed by their models affect billions of people. Private models often create predictions with high geographic granularity but little accuracy, and disparities between models reveal potentially inaccurate risk assessments, which especially impact vulnerable communities. To improve transparency, a standard-setting body to review private models or a public prediction system is needed.

Key Stakeholders in Parametric Insurance

In addition to regulatory bodies and risk modelers, stakeholders include parametric insurance buyers and providers.

Buyers

Buyers of parametric insurance range from homeowners in high-risk US states where traditional and last-resort insurers do not cover risks to farmers in drought-prone areas around the world. Buyers also include people with uninsurable assets and reinsurers, who buy insurance from other insurers, including agricultural and energy infrastructure businesses.

Providers

Established companies

Established insurance companies developing and underwriting parametric insurance policies for natural disasters, agriculture, and climate risks include Swiss Re, Munich Re, AXA Climate, Hiscox, and Lloyd’s of London.

Startups

There are several startups around the world expanding parametric insurance products.

Arbol, based in the US, underwrites parametric insurance policies that address six climate risks, including temperature, soil moisture, and solar radiation. They have clients of all types in over 15 countries, are profitable, and recently raised a $60M Series B round.

Descartes Underwriting, based in France, offers parametric insurance policies globally for climate risks, cyber risks, and other emerging risks.

Raincoat, based in Puerto Rico, offers parametric insurance policies globally for natural disaster risks. With new regulations in Puerto Rico, there are no longer proof-of-loss requirements and premiums must be at or below 2% of the minimum wage salary.

Floodbase, based in the US, offers parametric flood insurance to communities vulnerable to floods globally, including through parameter setting, trigger design, location data analysis, and continuous monitoring.

Jumpstart, based in the US, offers parametric earthquake insurance. To meet the proof-of-loss requirement, they text clients after a parameter is reached or exceeded asking whether they want their payout, regardless of damages.

Micro-insurance

The R4 Rural Resilience Initiative, backed by the World Food Programme (WFP) and Oxfam America, provides parametric micro-insurance policies for extreme weather triggered by rainfall levels. The initiative covers over 450,000 people in Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Senegal, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Sovereign Insurance

Two major regional risk pools are the Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF) and the ARC.

The CCRIF was founded in 2007 and offers parametric insurance policies to Caribbean and Central American countries for disaster responses to tropical cyclones, earthquakes, and excess rainfall. The member nations select their own trigger parameters and receive payouts within 14 days. CCRIF has disbursed around $390M, and is supported by the WFP and World Bank. China and India are now pursuing similar systems.

Africa loses up to 15% of its GDP per capita to climate shocks. The ARC, which was founded in 2012 and is supported by the IMF and World Bank, covers 135M Africans, mostly for severe droughts. Member nations determine their own parameters based on local risk assessments and receive payouts within 10 days. Some nations in the ARC, including Zimbabwe and Zambia, cannot borrow from multilateral lenders or global markets due to unpaid debt. The ARC therefore provides critical payouts.

What’s next?

To address the protection gap, we need a combination of strategies, including retrofitting homes, state-backed and non-admitted insurance, and adjusted premiums. Parametric insurance offers a key supplement to the market due to its efficiency and flexibility. The global market for parametric insurance grew to around $12B in 2021 and is projected to reach $29B by 2031.

Alongside designing and offering new insurance policy structures like parametric insurance, we must focus on preventing the disasters insurance covers from occurring. Cutting emissions today is like paying an insurance premium against climate risks. The more we reduce emissions, the less we will spend on disaster adaptation and recovery.

Bravo